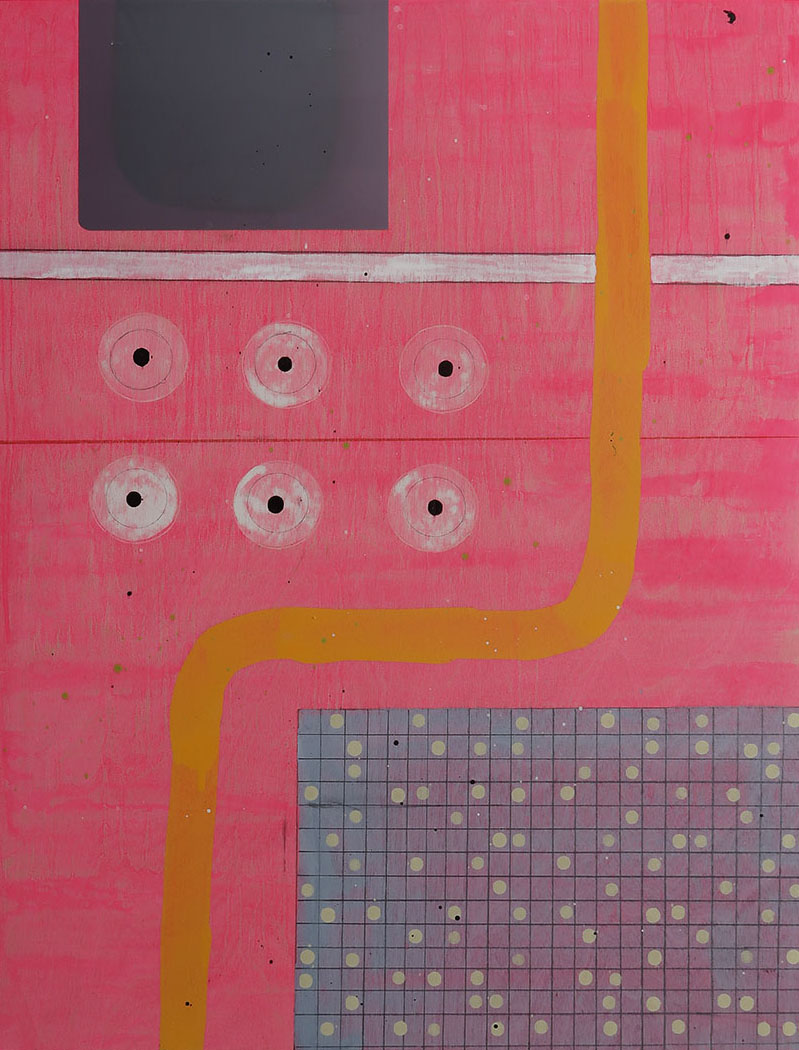

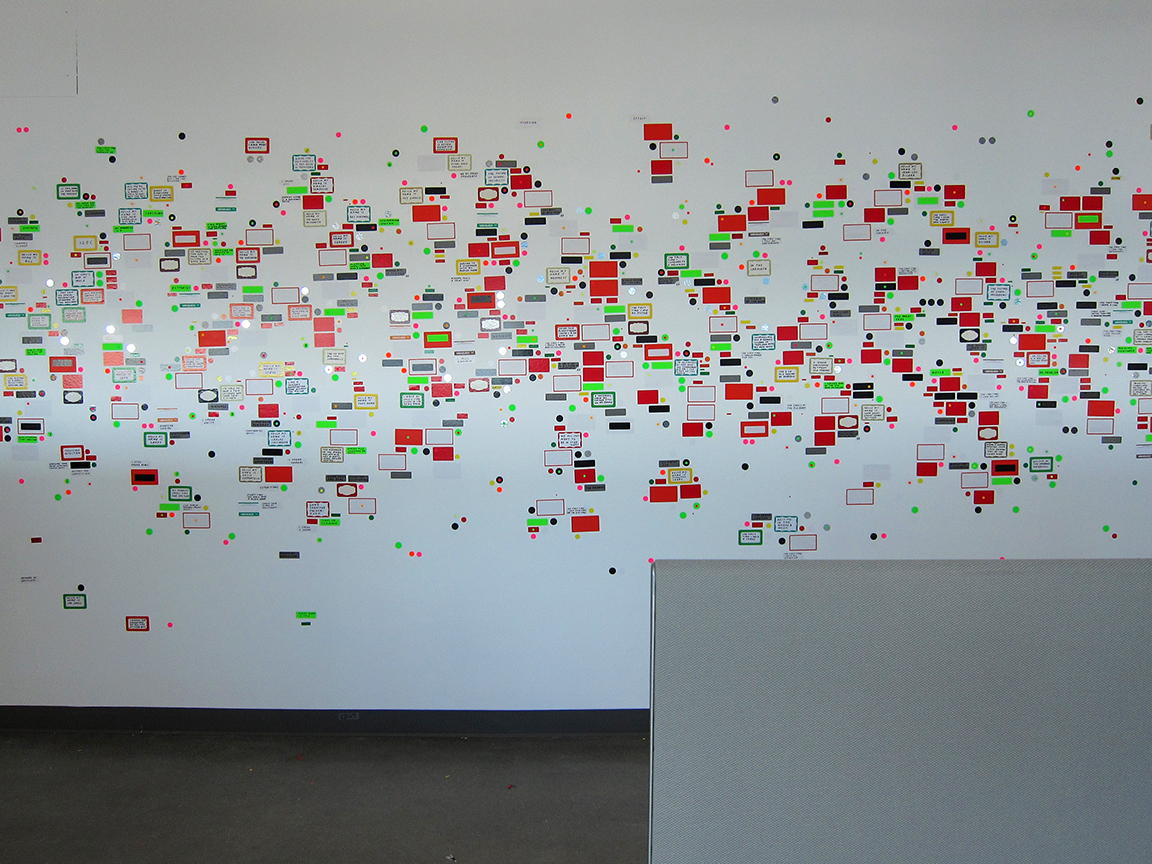

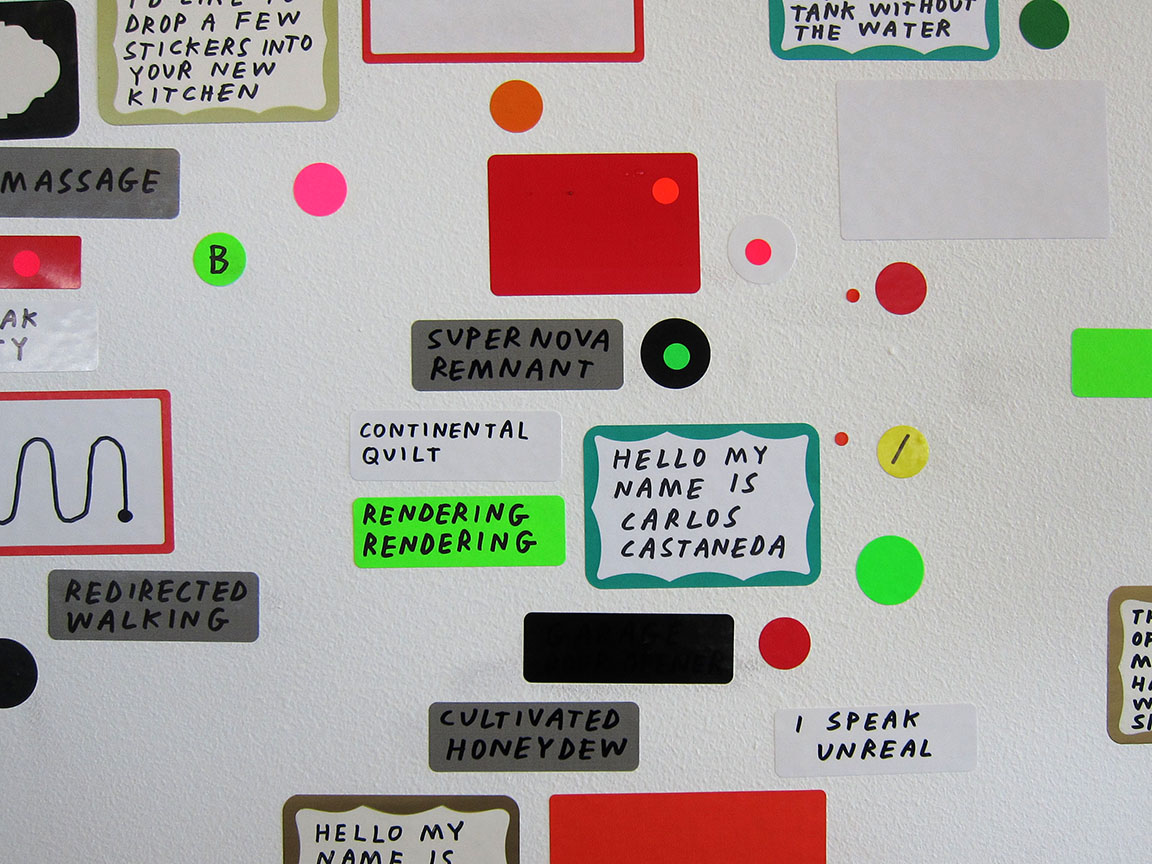

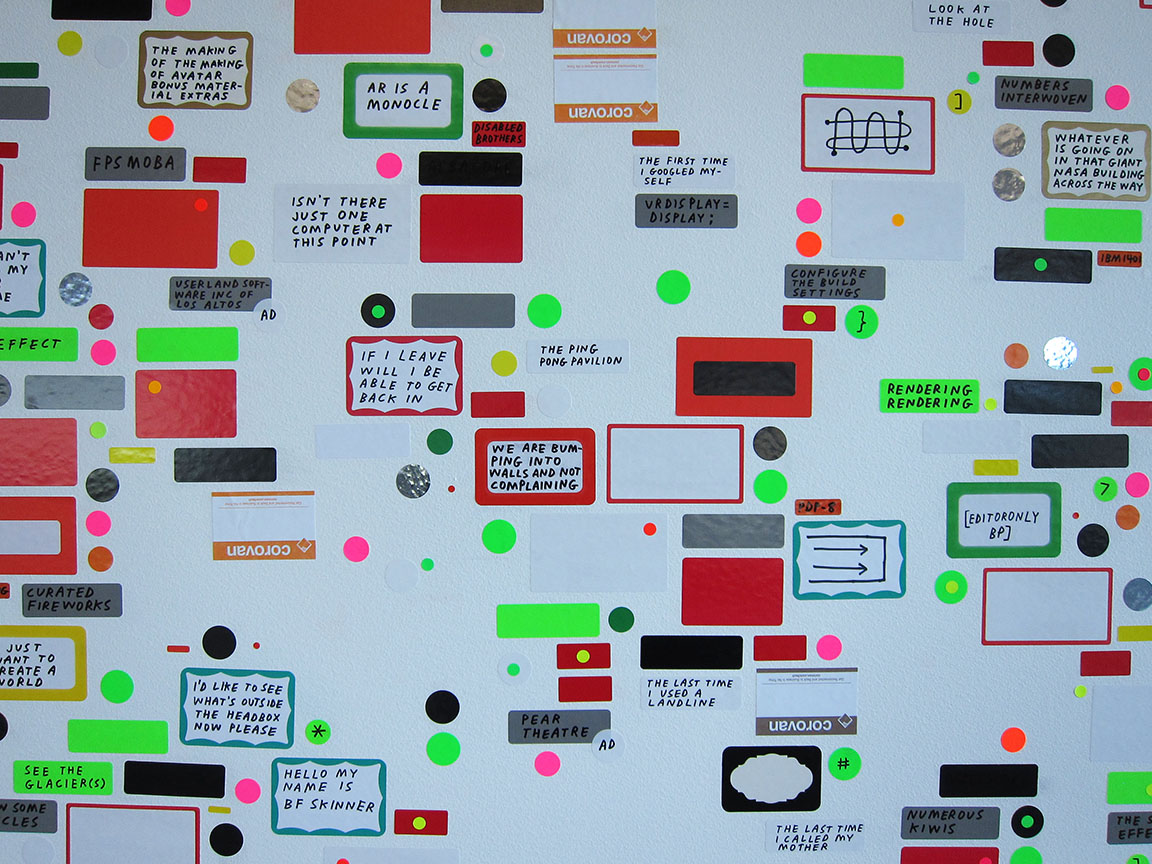

Nichols also uses print as a way to blur the distinctions between painting, the space it inhabits, and architecture. In 2011 the artist and Gallery 16 founder Griff Williams created a mural in the gallery by scanning a 5-by-7-inch ink-on-paper drawing at extremely high resolution, printing it digitally in long strips and affixing it like wallpaper to a 10-by-18 foot wall. The once hand-held image—blue dribbles over red, navy, aqua, pale yellow and orange washy stripes—now encompassed the viewer’s entire body. To have attempted to replicate the original small artwork on that scale would have required a kind of rigorous planning alien to Nichols’s spontaneous methods. “When you work small,” he says, “there’s more freedom. You would think the opposite, but that is not the case for me.” Enlarging the little watercolor changed it from one kind of thing into another, and he had no idea whether he would like it: “It’s riskier to work with something you are already familiar with and use it in a new way. The whole thing could have really failed the translation process.” In the end, he saw it as a success—an alternate way to view architectural space as a subject, and to recast the familiar in a different light.

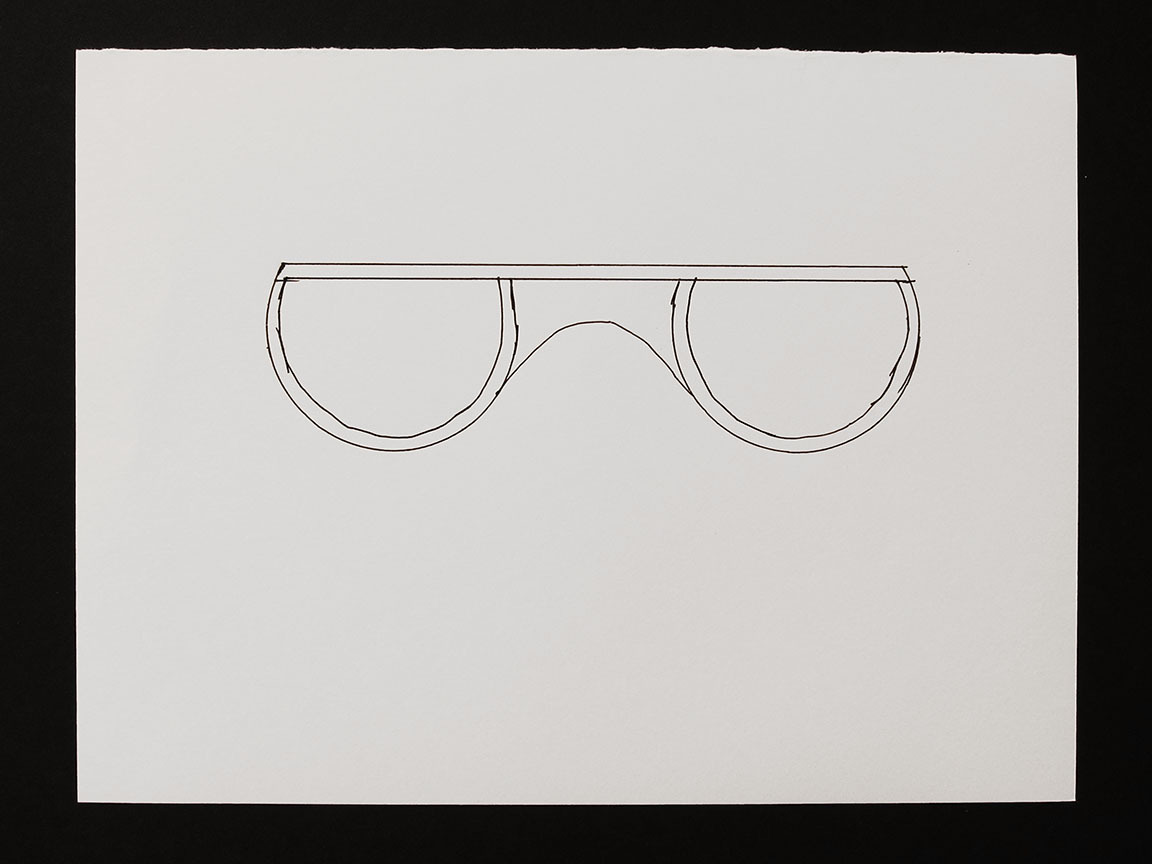

Printmaking—in the sense of traditional technologies and formats, limited editions and framed objects on a wall—is something Nichols approached with some hesitation. During my studio visit, he told me that “for the longest time I didn’t think that printing was for me.” As a child in Philadelphia, he had made linocuts, and returned to the medium briefly in 1990. His interest revived in the early 2000s, when he spent a couple of years learning lithography from his friend Michael Paler in San Francisco. (“We met weekly in the evening and often stayed up late into the night. The best kind of learning.”) And for several years now he has been working closely with screenprinter Nat Swope at Bloom Press in Oakland. The images begin as cut-paper collages or brush drawings on glossy paper (ensuring a crisp edge for his idiosyncratic lines), and are transferred to the template photographically. He sees prints as “a showcase, as opposed to a witness to a process” and appreciates the straightforwardness that one- or two-color printing imposes because clearly the “ink is there or not.” The result equalizes the foreground and background and, Nichols says, “emboldens” the subject, recasting it in “its flattest form,” a contrast to his often highly textured paintings.

Many of his prints feature flower arrangements similar to those of his paintings, but simplified and stripped of the thick textures and traces of the hand. Nichols has given serious thought to the problem of flowers—their visual power and the likelihood that they may be seen as nothing more than a limited delight. In the wake of the 2016 presidential election, he also began to question the utility of art more broadly: in his statement for his “Flowerland” exhibition in Los Angeles this past summer, he considered the respective roles of painting (especially floral painting) and political lawn signs, concluding that both “seem just as futile as they are hopeful.”4 The ambiguous import of flowers was also central to his September “Patio Music” exhibition at Gallery 16. The vague “nowhere” settings of his earlier still lifes have been replaced with implied environments: “Patios,” he explains, “are gathering spaces—like music—private, yet also public and social.” The works manifest how he views painting as an activity at the edges of personal privacy and social exposure: “I want to feel a little bit naked.” Formally his new work is a continuation of a group of 2016 works marked by their exuberant compositions. In a review in the Times, Roberta Smith spoke of their “modernity and joy” and of the autonomy of their separate parts: “the spherical flowers could easily bounce away; the bladelike leaves could launch themselves in one direction or another.”5

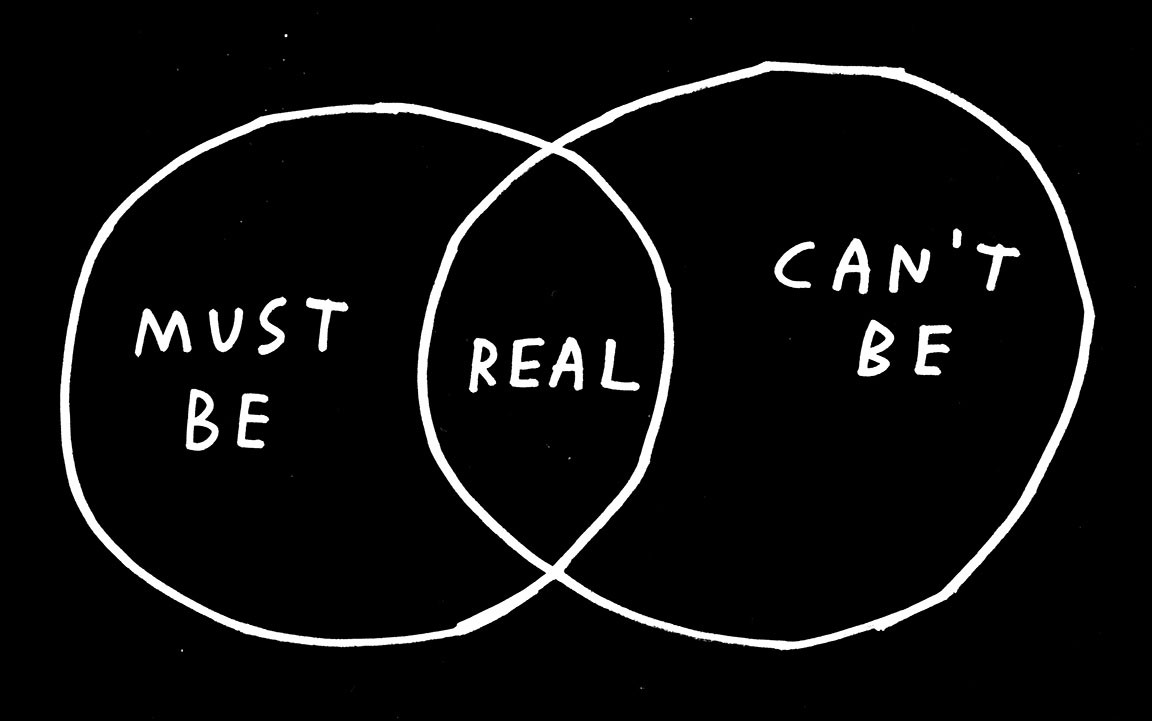

For all their visual pleasures, however, the plant and flower arrangements that have occupied his attention for so long are grounded in a personal and poetic investigation of how things carry meaning in the world. Having studied 10th-century Chinese bird-and-flower painting, Nichols is attuned to the iconographic opulence of plants—in China historically orchids might symbolize loyalty, bamboo strength and resilience, and pine trees endurance.6 In Western art history flowers have also been rife with meaning—just think of the plangent memento mori properties of Dutch 17th-century still-life paintings. What intrigues him most about flowers, however, is not the idea of a cultural code in which one thing directly signals another, but their gift for imprecision—the way we use them as stand-ins for things we don’t know how to articulate. “Think about why we give flowers to others,” he says. “Flowers do a bad job at saying something specific, but they do a really good job at saying something we can’t put into words.”

Nichols has spent many years in and out of hospitals; he has Crohn’s disease and is familiar with the suffering that goes on in sterile rooms with their colorful bouquets, meant to brighten spaces and lift spirits. His botanicals can be seen as metonyms for the emotions of giving and receiving, as can art: “I get an adrenaline rush from showing my work to others,” he says. The British critic and painter Roger Fry observed in his 1909 “An Essay in Aesthetics” that “It is only when an object exists in our lives for no other purpose than to be seen that we really look at it.”7 By their very existence, paintings, prints and other artworks—like floral bouquets themselves—are made to be seen for more than what they appear on the surface. At the heart of why Nichols makes things is the possibility of making someone’s day more pleasurable, amusing or contemplative, but the elusory meaning lurking within his subjects is what makes his work so unexpectedly poignant. “I love it when things are hard to grasp,” Nichols remarked in his studio, “something beyond the truth.”

In his 1836 essay “Nature,” Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote: “A man’s power to connect his thought with its proper symbol, and so to utter it, depends on the simplicity of his character, that is, upon his love of truth and his desire to communicate it without loss.”8 There is strength in the ability and desire to communicate unburdened by theory or pretense. Nichols falls into this category; he is unabashed in his persistent study of flowers, acknowledging both their perfunctory charm and their varied covert messages, speaking of joy as well as of the fragility of life.